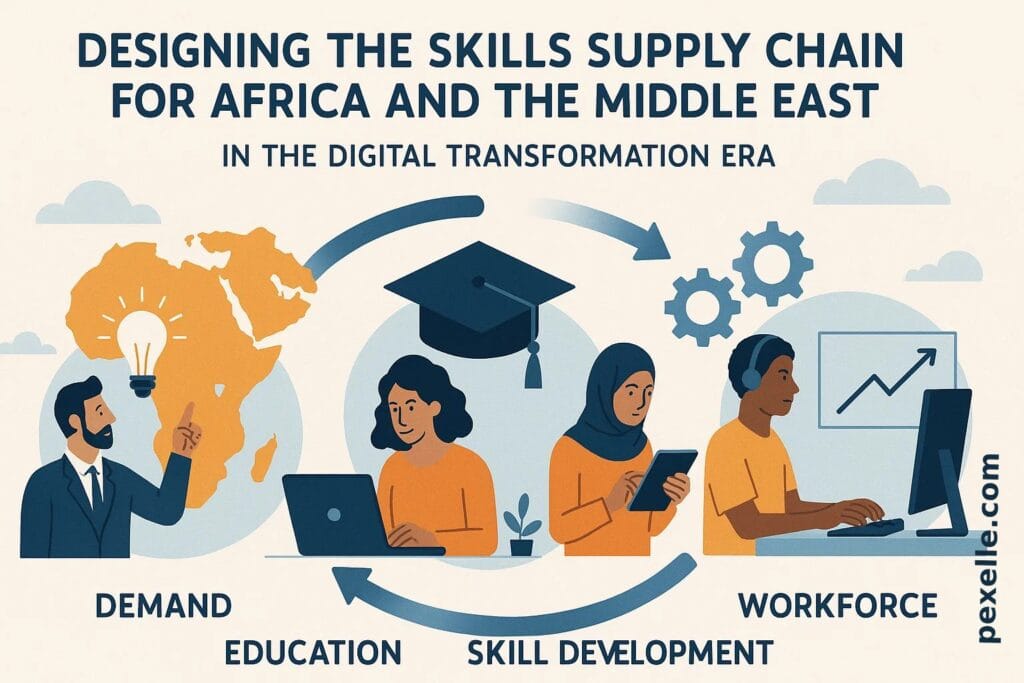

Designing the Skills Supply Chain for Africa and the Middle East in the Digital Transformation Era

1. Introduction: The New Battlefield of Skills

The global economy is entering a new phase where digital transformation and automation are redefining what nations need from their labor forces. For Africa and the Middle East, this shift is both an opportunity and a risk.

On one hand, the regions host the world’s youngest populations and are rapidly expanding their digital infrastructure. On the other hand, they face severe skills mismatches, fragmented education systems, and limited coordination between training institutions, industry, and policymakers.

To remain competitive and inclusive, these regions must design a modern skills supply chain — a connected ecosystem where education, technology, employers, and governance work as synchronized parts of a single system.

2. Understanding the “Skills Supply Chain”

Just as supply chains in manufacturing move physical goods from raw materials to final products, a skills supply chain describes how human capabilities flow from education and training systems to employment and innovation ecosystems.

It includes:

- Input stage: Foundational and digital education, early STEM exposure, and access to connectivity.

- Processing stage: Technical and vocational training, apprenticeships, and continuous upskilling programs.

- Output stage: Integration of skilled workers into jobs aligned with industry demand.

- Feedback loops: Real-time labor market intelligence that informs what skills need to be developed next.

In Africa and the Middle East, these chains are often broken or outdated — education systems produce graduates with theoretical knowledge but limited industry relevance, while employers struggle to fill roles in data analytics, AI, cybersecurity, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing.

3. The Pressure of Digital Transformation (2025 and Beyond)

The year 2025 marks a turning point. Emerging technologies like AI, robotics, quantum computing, and blockchain are moving from the pilot phase into full-scale adoption. According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2025 report:

- Nearly 44% of current skills will be disrupted within five years.

- Analytical thinking, technological literacy, and curiosity are now top priorities for employers.

- The fastest-growing roles in developing economies include AI engineers, digital marketers, cybersecurity analysts, and data translators.

For Africa and the Middle East, this disruption is amplified by demographic realities. Each year, over 12 million young Africans enter the labor market, while only 3 million formal jobs are created. Without re-engineering the skills supply chain, the region risks deepening its youth unemployment crisis — and losing the innovation potential of its young generation.

4. Case Study 1: Kenya’s Digital Talent Program

Kenya has emerged as a regional testbed for digital workforce development. Its Ajira Digital and Digital Talent Program aim to train thousands of youth in cloud computing, software development, and digital freelancing.

Strengths:

- Government–private partnerships (Google, Huawei, Microsoft).

- Integration of digital literacy in TVET and university curricula.

- Focus on gig economy readiness.

Weaknesses: - Limited scalability beyond urban centers.

- Poor coordination between county governments and national strategy.

Lesson: A digital skills initiative cannot rely solely on training. It must embed employer demand mapping, mentorship, and placement pipelines to function as a true supply chain.

5. Case Study 2: The UAE’s National Artificial Intelligence Strategy

The United Arab Emirates presents a contrasting model: top-down alignment and investment in future-skills ecosystems.

Key features include:

- The Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence (MBZUAI).

- National AI and coding bootcamps integrated with K-12 reforms.

- Mandatory AI and data analytics training across ministries.

The UAE demonstrates how strategic policy coherence and foresight can convert digital transformation into human-capital advantage. However, its model depends heavily on state funding and centralized governance, which may not be replicable across lower-income countries without adaptation.

6. Identifying the Core Skill Gaps

A 2025 analysis by the African Development Bank and the International Labour Organization highlights several urgent gaps:

| Sector | Critical Missing Skills | Emerging Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| ICT & AI | Cloud computing, data analytics, cybersecurity | AI policy, ethical design, quantum-safe cryptography |

| Renewable Energy | Green tech, maintenance engineering | Solar design, battery recycling |

| Agriculture | Precision farming, agri-data management | Smart irrigation, drone operation |

| Manufacturing | Automation, mechatronics | Additive manufacturing (3D printing) |

| Public Services | E-governance, digital identity | GovTech and blockchain transparency |

These gaps reflect not only a lack of training, but a lack of integration between data-driven labor forecasting and educational policy.

7. Structural Weaknesses in the Current Ecosystem

The core bottlenecks holding back a functional skills supply chain include:

- Fragmented governance: Ministries of Education, Labor, and ICT operate in silos, duplicating efforts.

- Data scarcity: Few countries maintain real-time labor-market information systems (LMIS).

- Private sector disengagement: Employers are rarely involved in curriculum design.

- Inequitable access: Rural learners, women, and informal workers are often excluded from reskilling initiatives.

- Short-term donor projects: Many digital-skills programs die when funding ends, leaving no sustainable infrastructure.

Without tackling these structural issues, even the best-intentioned skills programs become isolated experiments instead of systemic transformations.

8. Designing a Resilient Skills Supply Chain

To build a future-ready skills ecosystem, countries in Africa and the Middle East must adopt a value-chain mindset anchored in six principles:

- Demand-driven alignment:

Establish national digital skills observatories that continuously track employer needs and update curricula dynamically. - Integrated governance:

Create a Skills Coordination Council linking ministries, private-sector consortia, and academic institutions under a unified framework. - Micro-credentialing and verification:

Replace static diplomas with modular, blockchain-verified micro-skills — allowing learners to prove specific competencies quickly. - Public–private–academic collaboration:

Incentivize companies to co-design apprenticeships, while universities open data and research access to startups. - Digital inclusion:

Subsidize broadband and device access for under-represented groups; develop content in local languages. - Feedback and foresight:

Integrate AI-driven analytics to forecast upcoming skill demands (e.g., from renewable-energy expansion or quantum-security adoption).

9. The Role of Platforms like Pexelle

This is precisely where AI-powered skills intelligence platforms such as Pexelle can make a tangible impact.

Pexelle’s ability to analyze, tag, and verify micro-skills, aggregate labor-market signals, and match talent to future opportunities represents the backbone of a digital skills supply chain.

Such platforms can:

- Help governments visualize national skill inventories.

- Support universities and training centers to adjust curricula in real time.

- Enable employers to hire based on verified micro-credentials rather than traditional CVs.

- Empower individuals to build dynamic digital skill profiles aligned with both local and international demand.

By combining AI-driven analytics with blockchain-based verification, systems like Pexelle can ensure trust, transparency, and traceability in the human-capital pipeline.

10. Policy Recommendations

To turn the skills supply chain into a strategic asset, African and Middle Eastern nations should act on four levels:

A. National Policy

- Integrate skills intelligence into national digital-transformation roadmaps.

- Align educational budgets with priority sectors (e.g., AI, green energy, agritech).

- Establish incentives for private-sector co-funding of reskilling programs.

B. Institutional Strategy

- Embed skill-forecast dashboards in TVET and university systems.

- Adopt open digital-badging standards compatible across countries.

C. Industry Engagement

- Require large employers to publish annual “skills demand reports.”

- Create tax credits for companies that train or re-skill workers in priority fields.

D. Regional Collaboration

- Develop African–Arab Skills Corridors — joint frameworks for recognition of credentials, shared LMIS data, and cross-border mobility for skilled professionals.

11. Conclusion: From Potential to Performance

The next decade will decide whether Africa and the Middle East become producers or consumers of digital innovation.

Their success depends less on building isolated training programs and more on designing interconnected skills ecosystems capable of adapting in real time.

The question is no longer “What skills do we need?” but rather “How fast can we detect, develop, and deploy them?”

If these regions can build a coordinated skills supply chain — supported by data, technology, and trust — they won’t just catch up with the digital revolution; they’ll help define it.

Source : Medium.com